Dear readers,

Dear readers,

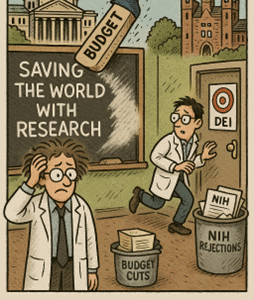

I don’t know about you, but I’m feeling a little bummed out about the current state of academia.1 Federal funding for important research is being cut, institutions like Columbia and Harvard are being harassed by an unusually handsy executive branch, and if you are a diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) researcher, I wouldn’t blame you for feeling like you have a target on your back.

Some grad students are going into the summer without knowing whether they will receive financial support in the fall. International students are facing tremendous uncertainty regarding their immigration status and may be cancelling plans to travel out of the country to visit their families for fear that they may not be able to return, or worse. I just had a conversation with an international grad student who described living in a constant state of fear of losing her visa due to a minor traffic violation that occurred several years ago.

Some grad students are going into the summer without knowing whether they will receive financial support in the fall. International students are facing tremendous uncertainty regarding their immigration status and may be cancelling plans to travel out of the country to visit their families for fear that they may not be able to return, or worse. I just had a conversation with an international grad student who described living in a constant state of fear of losing her visa due to a minor traffic violation that occurred several years ago.

Given the current administration’s hostility toward DEI and predilection toward inserting itself in extremely uncomfortable places (e.g., insisting on oversight of Columbia’s Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies department2), it’s not inconceivable that we could see executive orders that prescribe how we teach topics to do with race, identity, sexual orientation, and other areas that are (or become) politically disfavored. The situation looks so grim to me that I have begun advising international students who plan to apply for graduate school to strongly consider programs in other countries.

Along the same lines, SIOP felt different this year. The usual joyful reunion with old friends who I only see at SIOP was inevitably followed by a concerned discussion about the state of the country, leadership, federal funding, and attacks on academia, immigrants, the rule of law, and so forth. Strangely, I found these conversations to be a great comfort as our shared values as I-O psychologists were at the foundation of people’s reactions: We are committed to education, to research, to evidence-based decisions, to the truth, to diversity and human rights, and to competent leadership. These shared values arise less from ideology or dogma than from decades of research and practice in I-O psychology. Perhaps we all can benefit from a little pick-me-up concerning the work that we do as educators in the face of attacks against education.

Our Work Matters—Now More Than Ever!

As teachers, we have an opportunity to influence our students in profound ways that may benefit and inspire them for the rest of their lives. I’m sure we can all think of teachers who played a huge role in shaping our career paths and making us the people we are today. Looking back at my PhD program at the University of Akron, I think of countless meetings with my advisor, Bob Lord, who treated a kid who didn’t know anything as an equal with ideas worth listening to. I think of Paul Levy, from whom I learned so much about professionalism in the classroom (along with many other things). Andee Snell and Rosalie Hall taught me to love data and stats, a love which continues to this day. I think of Dan Svyantek and Dennis Doverspike, who showed how the field of I-O psychology is so much bigger than what’s in an intro textbook. And I think of Kevin Kaut, my neuroscience prof, who gave me sound advice when I was questioning whether I should forgo teaching for a year to work with Bob Lord on a research grant. His advice: “You’ll have lots of chances to teach classes in your career but not to work on a research grant with Bob Lord, a giant in our field, you idiot! He was kind enough not to say “you idiot!” out loud, but looking back, I’m certain that’s what he was thinking. I could go on. Whatever success I have had I owe to them and many others.

Please remind yourself that each class you teach is an opportunity to positively impact students, both in ways that you intended and ways that cannot possibly be anticipated that go far beyond the curriculum. On this latter point, I remember a Baruch undergraduate student coming to my office hours to ask how I, an immigrant like her, ended up in what, in her view, was such a vaunted position of societal importance and respect. She was the first student in her family to attend college and simply had no idea how higher education worked or where professors came from. I hope my answer helped her to understand that she can achieve her life goals as well. As I wrote in my last column, at the end of each semester, I ask students what material from the class they found the most (and least) valuable. I am often amazed at not just what students find valuable but also why. For example, conflict resolution is a topic in my undergraduate management/leadership class, which some students value not so much for their current or future work as managers but as a tool that they can use to navigate the generational family conflict that they are experiencing. We may think of ourselves primarily as conveyers of information, but in our students’ eyes, we may be role models, parent figures, confidants, cheerleaders, and trusted mentors whose impact goes well beyond the classroom. This is a privilege and a responsibility.

Percent of U.S. adults in Each Demographic Group Who Get News at Least Sometimes From…

|

Television |

Radio | Print publications |

Digital devices |

|

|

Ages 18–29 |

46 | 27 | 18 | 91 |

| 30–49 |

51 |

43 |

19 |

91 |

| 50–64 |

72 |

51 | 26 |

87 |

|

65+ |

86 | 43 | 43 |

70 |

Extracted from Pew Research Center (September, 2024) News Platform Fact Sheet3

As I-O psychologists, we have a lot to offer students, given the challenges that we are currently facing in the USA. The research skills we teach can help students to better process and evaluate claims, a critically important capacity for living in a confusing and disorienting media environment. Many of our students have grown up in a world where they do not rely on the nightly news to gain a clear sense of the state of the world and where much of the news reaches them through the lens of social media.4 Conducting a literature review, evaluating research findings against methodology, and considering the quality of sources of evidence that underlie claims—these are all skills that we teach in our classes that provide students with tools that can help them make sense of the world.

Teaching the value of DEI has perhaps never been more important since the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, given the many efforts to ban DEI programs5 and the ideological polarization around this issue.6 I had an undergraduate student who was a vocal supporter of President Trump ask me what I thought about “all of this DEI stuff.” I responded by saying that we should first be clear on what we mean by DEI. The “D” is for diversity. We know from research on team performance that diverse teams have long-term advantages over homogenous teams, in part because having a greater diversity of viewpoints is a resource that benefits decision making.7 Organizations value diversity because it provides tangible benefits to their bottom lines, among other reasons.8 Equity is about providing equal opportunities to all and helping people overcome barriers. We know that historically, in the USA, some groups have faced significant barriers (e.g., Blacks being enslaved, women not being allowed to vote, etc.) and that these barriers don’t go away by themselves. Inclusion is the idea that we should encourage and support participation in work by all parties, especially those who may encounter barriers that prevent them from participating. I asked him what about DEI he objected to. We had a productive conversation about the issues. I think he understood “DEI” initiatives to be the practice of hiring less qualified minorities and women over more qualified White people and men due to hiring quotas or decision makers’ biases against the majority group. I assured him that I would be against this as well and that such an approach would likely be unlawful. But I also suggested that his view of DEI was not a fair characterization of DEI goals or practices in general. You may have had a different set of answers than the ones I came up with, but what I imagine would be common of most I-O psychologists’ responses would be to (a) define constructs so we know what we are talking about, (b) review existing evidence and theory, and (c) form conclusions with an appropriate level of caution. I think it’s valuable to have these conversations with our students, though they can be difficult and scary.

I believe that our field tends to think about the psychology of work more from the perspectives of employers or organizations than from the perspectives of employees or the communities in which organizations operate.9 As such, we may have a tendency not to be too rebellious against these authorities, given that they tend to fund much of our work. Similarly, many I-O psychologists who teach have government contracts or relationships with government clients that they don’t want to jeopardize. There are, perhaps, more reasons now than ever before to keep one’s head down and avoid the roaming gaze of the executive branch.10 However, I hope that we will continue our duty to teach I-O psychology, even if some of our teachings run counter to prevailing political headwinds. The state of higher education in the USA is scary and dark right now. But that also means that the work we do can shed even more light.

As always, please email me to share your views, disagreements, experiences, or to just say hi: Loren.Naidoo@csun.edu

Notes

1 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-01289-4

2 https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/mar/21/columbia-university-funding-trump-demands

3 https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/news-platform-fact-sheet/

4 https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/news-platform-fact-sheet/

5 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/02/us/university-florida-dei.html

7 This was, inevitably, an oversimplification: e.g., van Knippenberg & Schippers (2007).

9 It’s always risky to make such a generalized claim, and you may disagree with me on this. There are certainly some trends in the opposite direction (e.g., well-being, DEI, work–nonwork interface). But I think the historical roots of our field and the fact that in most of the work that we do as I-Os, the client is the organization or the government entity, not the individual employee, support my view. I encourage you to read the work of my former colleague at Baruch College, Joel Lefkowitz (2008), and others like him who have argued (far more eloquently than I ever could) for a more humanist approach to I-O psychology.

10 E.g., I wondered whether writing this column was a smart thing to do. I guess I’m not that smart.

References

Lefkowitz, J. (2008). To prosper, organizational psychology should… Expand the values of organizational psychology to match the quality of its ethics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29 (4), 439-453.

van Knippenberg, D., & Schippers, M. C. (2007). Work group diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 515-541.

Volume

63

Number

1

Author

Loren J. Naidoo, California State University, Northridge

Topic

Publications, The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist