Correspondence regarding this article should be sent to Dr. Sayeedul Islam at Talent Metrics Consulting, 718 Walt Whitman Road, #861, Melville, NY 11747. sy@talentmetrics.io

Apocalyptic and postapocalyptic narratives mirror humanity’s deepest anxieties about survival, meaning, and the limits of social order. In the 21st century, the prevalence of postapocalyptic media has intensified, revealing collective fears about ecological collapse, pandemic contagion, and systemic fragility (Dickey, 2020; Moon, 2014). These narratives provide more than escapist entertainment; often, they function as laboratories for examining the reconstruction of meaning, leadership, and community in crisis (Roberts, 2020). Nuclear scientists even use a doomsday clock as a measure of dangers within their field of work (Sinclair & Silbersweig, 2025). The postapocalyptic imagination thus offers fertile terrain for industrial-organizational (I-O) psychology, a discipline that seeks to understand how people work together, make ethical choices, and sustain motivation in the world of work.

I-O psychology is itself at a crossroads, facing critiques of fragmentation, overtheorization, declining practical relevance, and concerns around educating the next generation of the field (Dillon et al., 2023; Lefkowitz, 2010; Ones et al., 2017). As workplaces undergo rapid technological, environmental, and existential disruptions, the postapocalyptic metaphor gains new relevance for the study of adaptation, resilience, and leadership under uncertainty. Recent analyses underscore how I-O psychology must evolve to meet volatile political and policy environments that threaten organizational ethics, worker rights, and scientific integrity (Katz & Rauvola, 2025). Future-oriented organizational methods—such as future-oriented job analysis (Landis et al., 1998)—already emphasize anticipation and adaptability, yet even these approaches assume a baseline of stability that postapocalyptic frameworks challenge. In imagining organizations stripped to their human core—resource scarcity, moral ambiguity, and emergent hierarchies—postapocalyptic I-O psychology invites inquiry into what remains essential about work and leadership when formal structures collapse.

Popular culture has long shaped and reflected our understanding of organizational life. From The Office to The Walking Dead, media texts both parody and theorize human behavior in systems of power, meaning, and control (Mitra & Fyke, 2017; Rhodes & Westwood, 2008). These cultural artifacts can serve as pedagogical tools, what Maudlin and Sandlin (2015) call pop culture pedagogies. These tools teach audiences how to think about authority, cooperation, and identity. In postapocalyptic media, the collapse of civilization becomes a crucible for studying informal leadership, collective efficacy, and group adaptation; all core I-O concerns rendered visible through crisis storytelling (Rehn, 2008). Pop culture is already being used in I-O classrooms and training courses to teach concepts such as leadership (Schmidt et al., 2025) and to disseminate core I-O concepts to lay audiences. As such, using a popular culture lens on organizational scholarship and practice can challenge I-O psychologists to confront questions of ethics, identity, and survival in extreme conditions.

The relevance of such a lens is magnified by real-world global transformations. The intersection of work, sustainability, and the climate crisis, for example, is redefining occupational competencies and workforce demands (Krasna et al., 2020; Rose, 2014). Rose argued that I-O psychology can serve as a bridge between environmental sustainability and strategic human resource management, cultivating “green knowledge” and organizational readiness for eco-conscious change. In this light, postapocalyptic scenarios can be understood as psychological laboratories for resilience—spaces that dramatize how ecological degradation and social breakdown test the limits of leadership, learning, and ethical adaptation.

Other changes specific to the world of I-O psychologists are impacting how the practice of I-O is conducted. Recent changes in the federal government have caused many I-O psychologists to experience massive changes in a short period of time. I-O psychologists have seen pushback against traditional areas of practice, such as DEI training and traditional talent management strategies (Keith et al., 2025; SIOP, 2025). In addition, many I-O psychologists have lost jobs in government cuts due to a contracting economy (Katz & Rauvola, 2025). Abrupt changes in legal guidelines can cause major issues in a field governed by legal statutes (Hanges et al., 2013). These challenges mirror the challenges that organizations are facing in this new legal environment.

As organizations navigate unprecedented times in a VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) environment, the demands upon I-O psychologists will increase. From pandemics to environmental degradation, the future of work increasingly resembles the chaotic, decentralized, and morally ambiguous structures characteristic of postapocalyptic fiction. By considering these imagined futures, I-O psychology may anticipate and prepare for emergent psychological and organizational realities. In this way, a postapocalyptic perspective is not merely speculative; it may prove diagnostic and preparatory. It compels I-O psychology to confront its own existential questions: What does leadership mean when systems fail? How do values endure when institutions vanish? And how can psychological science help rebuild meaning, collaboration, and ethical responsibility in the aftermath of disruption? By considering a postapocalyptic I-O psychology, we reframe the field and ask ourselves how we can be reflective and resilient while maintaining the field’s core identity.

Questions around the core identity of I-O psychology can be found within recent commentaries and critical analyses. These commentaries highlight some concerns about the core nature of our science and practice (Rotolo et al., 2018) as anti-I-O practices take hold. Rotolo et al. recommended looking at expanding areas of practice that include the future, even a postapocalyptic one. Another perspective brought forth by Mumby (2019) questioned the very nature of work and presented a Marxist perspective on work and I-O psychology. Lefkowitz (2019) responded to Mumby’s work by asserting that I-O psychologists may not be familiar with the nature of capitalism and should engage with the injustices of capitalism. Rarely do I-O psychologists look at the field outside of the frame of the present (capitalist or otherwise). The present study sought to assess I-O psychology outside of its current perceived capitalist framework. Studies in social psychology have successfully used postapocalyptic worlds and fiction as a way to understand psychological phenomena (Vezzali et al., 2021) and may help the present study consider I-O psychology through a unique lens. Other fields, such as leadership development, have also seen value in using popular culture frameworks as a developmental tool (Schmidt et al., 2025).

The present study attempted to understand what I-O psychologists perceive to be the value of I-O psychology in a world without the expected technology, legal structure, and corporate attitudes that I-O psychologists have come to expect. Inspired by the work of Rudolph et al. (2021), where researchers evaluated the impact of the pandemic on I-O psychology, and following the work of Vezzali et al. (2021), the researchers use postapocalyptic narratives to allow I-O psychologists to explore the meaning of their work outside of a traditional modern-day, capitalist framework.

Method

An online survey was developed to assess I-O psychology practitioners’, academics’, and students’ perceptions of I-O practice in a postapocalyptic world. Participants were contacted by email and social media (LinkedIn) by the researchers and asked to participate in the study, resulting in 115 participants. The complete survey can be found in Appendix A. Fifty-seven percent of participants worked primarily as practitioners, 21% were current students, and 20% were in academic positions. Two percent of participants placed themselves in roles outside of these three categories into the category of “other.”

Participants were initially asked to describe the postapocalyptic world that they envisioned in responding to the survey. Participants were then asked to articulate how they felt I-O psychologists could contribute to a postapocalyptic world. These two questions were meant to allow participants to consider a postapocalyptic world before answering the final question in the survey. The final question involved rating the viability of different areas of I-O psychology practice based on the SIOP’s Education and Training Guidelines core content (SIOP, 2016). Participants were asked to rate I-O tasks like benefits/compensation/payroll, teamwork, and leadership.

Content Analysis Method

Qualitative data were content analyzed by a graduate-level research assistant and a PhD-level researcher. Using a grounded theory approach to qualitative content analysis, the research assistant read through the comments and identified themes, which were then reviewed by the PhD-level researcher (Cho & Lee, 2014). Qualitative data were also analyzed using computer-assisted text analytic tools, such as Voyant Tools and ChatGPT. As outlined by Wachinger et al. (2025), ChatGPT can be used along with other text analytic tools and human researchers to triangulate the meaning of a corpus. Triangulation refers to a combination of methodologies (Jonsen & Jehn, 2009), analytic tools (Bijker et al., 2024), and data sources (Carter et al., 2014; Cope, 2014) used to analyze a corpus of text. The present study used both human researchers and computer-assisted text analytic (CATA) tools, such as Voyant Tools and AI, to conduct analysis on the data collected.

Results

Participants’ responses to the question regarding the type of postapocalyptic world they envisioned were content coded for the type of postapocalyptic world mentioned by a graduate-level I-O researcher. The coding was discussed with a PhD-level researcher until consensus was achieved. The I-O researchers counted the number of times different postapocalyptic worlds were mentioned by participants. These data are summarized in Table 1. The Walking Dead was mentioned the most times, with Mad Max and The Last of Us tied with 10 mentions. A variety of other pop culture topics were mentioned just once, such as The Terminator, Borderlands, The Hunger Games, and The Parable of the Sower.

Table 1

Post Apocalyptic Worlds Mentioned

| Type of postapocalyptic world |

Number of times mentioned in responses |

| The Walking Dead |

13 |

| Mad Max |

10 |

| The Last of Us |

10 |

| Fallout |

7 |

| Pandemic |

7 |

| The Road |

4 |

| AI |

3 |

The corpus was analyzed by ChatGPT using the prompt “analyze this corpus for themes and topic modeling by LDA”. ChatGPT has been used to analyze text and has been found to be a comparable text analysis method to other CATA tools (Khan et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2023). ChatGPT was prompted to analyze the corpus for themes using topic modeling with Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) and provide example statements from the corpus. Topic modeling with LDA is defined as “computational content-analysis technique that can be used to investigate the ‘hidden’ thematic structure of a given collection of texts” (Maier et al., 2018). These themes, along with representative quotes from the corpus, can be found in Table 2 and include such themes as infrastructure collapse, resource scarcity, tribalism, pandemics, and climate collapse. These themes seem to indicate the worst endpoint of many of the current challenges faced by the world today, from phenomena such as climate change.

Table 2

Major Themes in Corpus of Postapocalyptic Visions

| Major theme | Description | Example (excerpt) |

| Infrastructure collapse/ technological failure | Power grids, internet, supply chains, and modern logistics fail (EMPs, solar flares, generalized tech failure). | “All technology fails and there is no electricity.” |

| Resource scarcity and competition | Shortages of water, food, medicine, fuel; barter economies, raids, and violence over essentials. | “War over water… key resources have become scarce and the remaining people need to band together.” |

| Tribalism/fractured society |

Collapse of national government; rise of tribes, communes, warbands, local power structures or corporate city-states. | “Society has splintered into tribes and scavenger enclaves.” |

| Pandemic/biological collapse & zombies | Disease-driven collapse or “infected” scenarios (fungal/viral vectors; slow/fast infection dynamics). | “I think The Last of Us most accurately depicts… fungal takeover.” |

| Nuclear fallout/war | Radioactive wasteland, long-term environmental uninhabitability and fallout effects. | “Nuclear holocaust… Most humans have died… coastal lands uninhabitable.” |

| Climate collapse/environmental disaster | Extreme heat, sea-level rise, drought, flooding, mass migration, food system failure; often tied to critique of capitalism. | “Climate change-induced—deserts, deadly heat, flooding, food scarcity.” |

| AI/technofeudal/post-singularity | AGI takeover or corporate technofeudal city-states; economic collapse due to automation. | “Post singularity collapse… mega corporations running city-states… technofeudal slave states.” |

| Desolate/ruined urban imagery and nature reclaiming cities | Empty skyscrapers, vines, silent streets, and nature overtaking built environments. | “Skyscrapers stand hollow, taken over by vines and shattered glass… nature has reclaimed what we left behind.” |

| Cultural motifs and reference anchors | Canonical media used as anchors for imagined worlds (e.g., The Last of Us, Mad Max, Fallout), shaping tone and specifics. | NA (multiple media references across responses) |

| Human dynamics and ethics | Distrust, loss of law, survivalism, tensions between hoarding and cooperation; ethical/regenerative possibilities. | “Survival depends on guarding what you have, but thriving depends on finding the courage to share it.” |

Participants were also asked how an I-O psychologist might contribute to a postapocalyptic world. Participants provided open-ended responses that were coded for common I-O skills by a graduate-level researcher and reviewed by a PhD-level researcher until consensus was achieved. Table 3 contains these skills and the number of times each skill was mentioned in the qualitative data. The top three skills mentioned were job assignment/selection, training, and team development.

Table 3

I-O Tasks Mentioned

| Type of I-O task |

Number of times mentioned |

| Job assignment/selection |

39 |

| Training/development |

35 |

| Team development |

27 |

| Organizational development |

20 |

| Leader development |

20 |

| Skill assessment |

18 |

| Consulting/expertise |

13 |

| Conflict management |

12 |

| Motivation |

11 |

Voyant tools were used to analyze the corpus (Sinclair & Rockwell, 2016). This tool has previously been used to analyze text in prior studies (Islam et al., 2022) and found to be effective. The corpus was organized into an overall corpus, academic respondents, practitioner respondents, and student responses. Each corpus was analyzed for the top five words using Voyant tools. The results of this analysis can be found in Table 4. The word “world” was common across all respondents. Academics seemed to focus on climate, whereas practitioners used the phrase “walking dead” more than students or academics.

Table 4

Top 5 Words Postapocalyptic World Description

| Overall corpus |

Number of times words appears |

Academic | Number of times words appears | Practitioner | Number of times words appears | Student |

Number of times words appears |

| world |

89 |

world | 5 | world | 26 | resources |

7 |

| post |

44 |

post | 4 | post | 15 | world |

6 |

|

people |

44 | climate | 4 | apocalyptic | 12 | post | 5 |

|

apocalyptic |

40 |

think |

3 | dead | 12 | apocalyptic |

5 |

|

resources |

38 | life | 3 | walking | 10 | scarce |

4 |

Table 5 contains a Voyant tools analysis of the top words used in the question about I-O tasks in a postapocalyptic world. With the major focus of the overall corpus being on helping people. Training appeared as a most often used word in the sub-analyses by academics, practitioners, and students. Practitioners and students focused on survival.

Table 5

Top 5 Words I-O Tasks

| Overall corpus |

Number of times words appears |

Academic | Number of times words appears | Practitioner | Number of times words appears | Student | Number of times words appears |

| people | 79 | Leadership | 7 | training | 13 | people | 8 |

| help | 56 | skills | 6 | roles | 8 | training | 7 |

| world | 49 | training | 5 | teams | 7 | new | 7 |

| skills | 49 | psychologists | 4 | systems | 7 | teams | 5 |

| psychologists | 40 | Work | 3 | survival | 7 | survival |

5 |

ChatGPT was used to analyze the corpus of responses to the question about I-O tasks in a postapocalyptic world. The results of the analysis are presented in Table 6. ChatGPT was prompted to use topic modeling LDA to analyze this corpus for themes. Common themes identified by ChatGPT include organizational design, training and reskilling, practical usefulness and limitations, and skepticism about survival. The analysis indicated that some I-Os were skeptical regarding the usefulness of their skillset in a postapocalyptic world. While the skills that were seen as useful were core skills in I-O, such as organizational design, training, and leadership development. There was some concern about the use of I-O psychology toward negative or harmful purposes (i.e., serving a warlord).

Table 6

Top Themes, Sentiment Valence, and Illustrative Examples

| Theme | Sentiment | Description | Example excerpt |

| Rebuilding and organizational design | Positive/ constructive |

I-O work viewed as essential for rebuilding society, including job analysis, role assignment, organizational structure, and succession planning. | “They could create the ideal organizations and teams… competency models and selection from the beginning.” |

| Training, reskilling, and knowledge transfer | Positive | Emphasis on rapid skill development, onboarding, cross-training, and preservation of institutional knowledge. | “Training programs for these roles… cross-train all members to create redundancy.” |

| Team dynamics, leadership, and morale | Positive/ practical |

Focus on trust building, conflict resolution, leadership coaching, and maintaining morale or mental health. | “They would help groups navigate forming connections, fostering trust deliberately and sustainably.” |

| Practical limitations and immediate usefulness | Cautious/ negative |

Limited usefulness in the immediate aftermath; lack of tools and greater need for physical survival skills. | “I don’t think our stuff generalizes to circumstances that extreme… we’d be of more help by learning to fight, gather food…” |

| Ethical concerns and co-option by power | Concerned/ negative | Risk that I-O expertise could be used to enhance exploitation or support authoritarian systems. | “Advising warlords how to be most effective in getting productivity out of serfs. Taylorist practices.” |

| Utility for governance and resource allocation | Positive/ practical |

I-O seen as helpful for designing fair systems for rationing, distribution, and structured community functioning. | “I think I-O psychologists could be helpful in organizing the structure needed for people to contribute… and the rebuilding of society.” |

| Skepticism about status and survival | Mixed (resigned/humorous) | Doubts about survival or usefulness of I-Os; humorous commentary about low status in collapse conditions. | “Oof, I honestly think we would be some of the first to be offed.” |

| Data/analytical value | Positive but contingent | Analytical skills remain valuable (pattern detection, manual assessment) but are hindered by technological loss. | “Data skills good for sorting truth/rumor, looking for patterns important to survival…” |

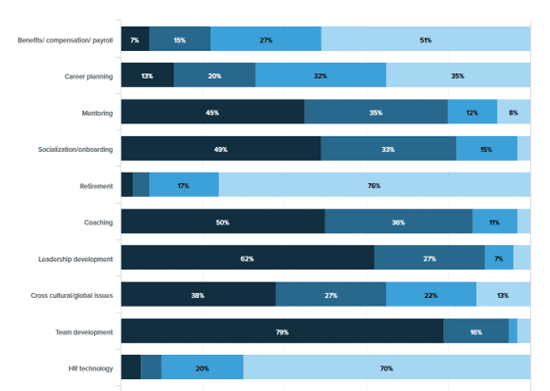

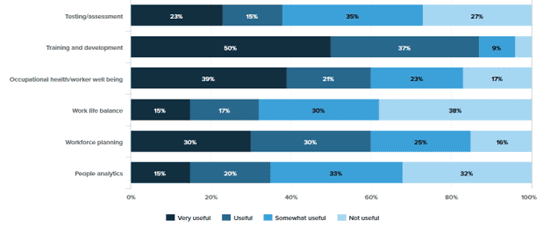

Figure 1 contains the percentage usefulness rating for all I-O tasks. Participants rated usefulness on a 4-point Likert scale with scale points: very useful, useful, somewhat useful, and not useful. Team development, leadership development and training were rated the most useful during a postapocalyptic world. HR technology was the lowest rated I-O task.

Figure 1.

Usefulness Ratings Overall by I-O Task

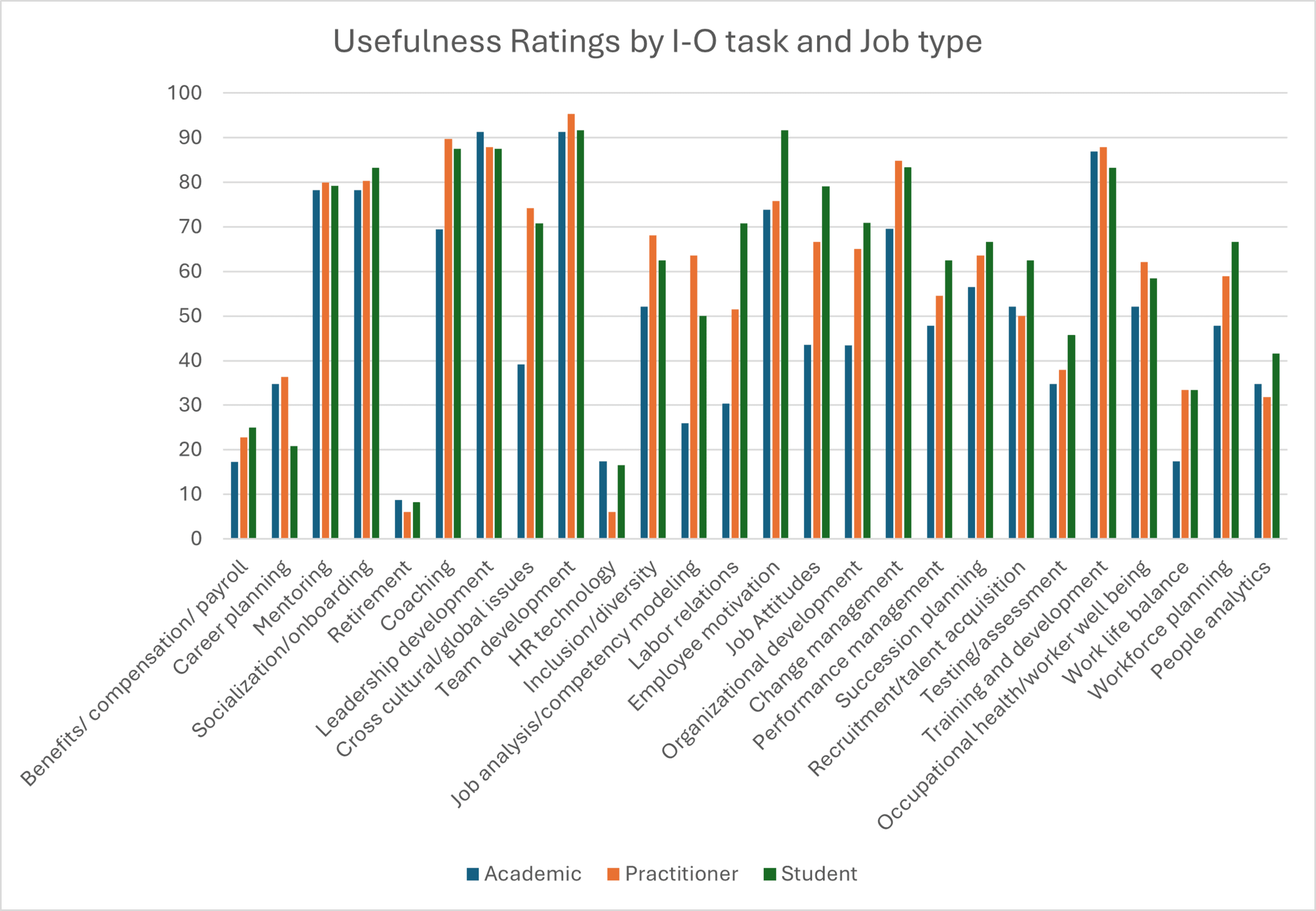

Figure 2 shows usefulness ratings by I-O task in bar chart form by the role of the participants (academia, student, or practitioner). Usefulness scores were calculated by adding the top 2 boxes (very useful and useful) to better indicate the level of agreement on a task. Results reveal that participants saw retirement as the least useful task, along with HR technology, benefits, compensation, and payroll.

Figure 2 shows usefulness ratings by I-O task in bar chart form by the role of the participants (academia, student, or practitioner). Usefulness scores were calculated by adding the top 2 boxes (very useful and useful) to better indicate the level of agreement on a task. Results reveal that participants saw retirement as the least useful task, along with HR technology, benefits, compensation, and payroll.

Figure 2.

Usefulness Ratings by I-O Task

Table 7 breaks down the data by the participants’ role (academic, practitioner, or student) and reveals some interesting trends. Ratings of high usefulness were similar across academics, students, and practitioners in five areas: mentoring, socialization, leadership development, team development, and succession planning. Some notable exceptions include job analysis/competency modeling, which was rated lower in usefulness by academics than by practitioners and students. Practitioners rated job analysis’ usefulness higher than both students and academics, cementing it as a key skill for practitioners even in a postapocalyptic world. Academics also rated tasks like labor relations, job attitudes, and organizational development as less useful in a postapocalyptic world than practitioners or students. Practitioners and students also rated activities like cross-cultural issues and inclusion higher than academics. As a general trend, students tended to rate all tasks highly in terms of usefulness. This may indicate a lack of experience with these tasks. Academics rated leadership development’s usefulness slightly higher than students and practitioners did. Practitioners and students rated coaching higher than academics did and had similar scores on benefits, cross-cultural issues, inclusion, occupational health and work–life balance. Academics and students rated HR technology similarly, but nothing else, perhaps indicating a deeper difference in perspective. HR technology was rated lower in usefulness by all categories, with practitioners seeing it as the least useful.

Table 7

I-O Task Usefulness Percentage by Job Type

| I-O skill | Academic | Practitioner | Student |

| Benefits/compensation/payroll | 17.3 | 22.8 | 25 |

| Career planning | 34.8 | 36.4 | 20.8 |

| Mentoring | 78.3 | 80 | 79.2 |

| Socialization/onboarding | 78.2 | 80.3 | 83.3 |

| Retirement | 8.7 | 6 | 8.3 |

| Coaching | 69.5 | 89.7 | 87.5 |

| Leadership development | 91.3 | 87.9 | 87.5 |

| Cross cultural/global issues | 39.1 | 74.2 | 70.8 |

| Team development | 91.3 | 95.4 | 91.7 |

| HR technology | 17.4 | 6 | 16.6 |

| Inclusion/diversity | 52.1 | 68.1 | 62.5 |

| Job analysis/competency modeling | 26 | 63.6 | 50 |

| Labor relations | 30.4 | 51.5 | 70.8 |

| Employee motivation | 73.9 | 75.8 | 91.7 |

| Job attitudes | 43.5 | 66.7 | 79.1 |

| Organizational development | 43.4 | 65.1 | 70.9 |

| Change management | 69.6 | 84.9 | 83.4 |

| Performance management | 47.8 | 54.5 | 62.5 |

| Succession planning | 56.5 | 63.6 | 66.7 |

| Recruitment/talent acquisition | 52.1 | 50 | 62.5 |

| Testing/assessment | 34.8 | 37.9 | 45.8 |

| Training and development | 86.9 | 87.9 | 83.3 |

| Occupational health/worker well-being | 52.1 | 62.1 | 58.4 |

| Work—life balance | 17.4 | 33.4 | 33.4 |

| Workforce planning | 47.8 | 59 | 66.7 |

| People analytics | 34.8 | 31.8 | 41.6 |

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to explore how I-O psychologists perceive the usefulness of their field in a postapocalyptic world. Drawing upon postapocalyptic narratives as both metaphor and analytic framework, this research sought to illuminate what practitioners, academics, and students consider essential to I-O psychology work under extreme conditions without modern tools (i.e., technology, AI). The findings reveal that although technological and structural components of I-O practice may lose value in postapocalyptic settings, the human-centered skills that form the discipline’s ethical and relational core, that is, leadership development, teamwork, and training, remain highly relevant no matter the context. The present study contributes a new perspective to studies of the future of I-O psychology and an understanding of the value of the field of I-O psychology overall.

Enduring Value of Human-Centered Competencies

Across participant groups, training, team development, and leadership development were rated as the most useful domains in a postapocalyptic context. These findings suggest that I-O psychology’s greatest contribution may lie not in its reliance on formal systems or data infrastructure but in its ability to cultivate shared mental models, shared purpose, and skill development, even during times of uncertainty. This finding aligns with existing calls for the field to return to its humanistic roots (Lefkowitz, 2008) and to integrate ethics and values more directly into practice (Katz & Rauvola, 2025). In environments where formal HR systems collapse, the ability to identify potential, organize collective effort, and sustain motivation becomes the new foundation for survival and social reconstruction. These are all human capabilities that remain at the core of I-O psychology’s identity, no matter the context.

We would also like to echo the calls from Lefkowitz (2008) and others that there needs to be a shared set of values to guide I-O psychology science and practice. Some of the responses to what an I-O psychologist would do in a postapocalyptic world surprised us with their frankness around supporting negative or potentially harmful outcomes. I-O psychology should always be guided towards the good of humanity, and an enshrined set of values would help to guide science and practice in that direction.

Differences Among Practitioners, Academics, and Students

Although general trends were consistent, nuanced differences emerged among subgroups. Practitioners tended to rate applied skills—such as job analysis and change management—more highly than academics or students, reflecting their emphasis on immediate utility and problem solving. Academics, by contrast, rated some organizational and attitudinal constructs (e.g., job attitudes, labor relations) and cross-cultural issues as less useful, possibly viewing them as luxuries of stable times rather than necessities during crisis. Interestingly, academics rated HR technology higher than practitioners. This may indicate an unfamiliarity with HR technology or an overestimation of its worth even in a postapocalyptic setting. These distinctions underscore the various perspectives within I-O psychology between scientist and practitioner. Student ratings were generally high, perhaps due to a lack of experience. This seems to indicate the importance of practical experiences for students, especially those coming from online programs where such experiences may be rare (Islam et al., 2022; Landers, 2017).

What Comes After the Apocalypse?

Although there is always great anxiety about the future of I-O (Bal et al., 2019), there is much hope in the usefulness of the field of I-O psychology. Even without technology or the trappings of the modern world, the community of I-O psychology instructors, practitioners, and students can find ways to contribute. Academics and practitioners should work together to find new opportunities for I-O psychologists. As the world faces numerous challenges and the economy continues to change our field, we must find new ways to apply our knowledge to the changing world of work. Although the authors of this article do not expect to face a postapocalyptic future, it would behoove the I-O psychology community to develop new models of thinking about the work of I-O psychology and to approach future projects with a wider lens of what the field is capable of. Recent calls for the study of concepts such as decent work, meaningful work (Blustein et al., 2023), gig work (Cropanzano et al., 2023), child labor (Fletcher, 2025), and public policy (Follmer et al., 2024). Expanding the field into every area where work is relevant will yield more research opportunities and allow the field to generate meaningful impact.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study includes several limitations. First, the sample size and sample collection method were mostly through those who were contacted by the researchers directly. Additional data collected from a wider range of I-O psychology practitioners, academics, and students may yield more generalizable results. Asking participants to imagine a future setting may not be the best method to elicit the response and consideration needed for this study. Future studies may wish to use other methodologies (i.e., focus groups) to understand what value I-O psychology may have in other settings and environments. Even a future job analysis for an I-O psychologist may prove valuable to the questions posed in this study.

Future work by SIOP or other interested researchers may involve imagining how I-O psychology’s capabilities can be utilized in a variety of contexts. Studies explicitly asking about the ways in which I-O psychology can support a world during climate change, war, famine, or pandemics may prove a valuable exercise for the field. Conducting simulation studies or working on projects in non-WEIRD (western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) may provide deep insights into what can be done with the science of I-O. Humanitarian work psychology provides a key opportunity here for students, academics, and practitioners to expand the field’s impact (Carr, 2025). We would also encourage the use of and reflection on popular culture as a medium for science communication, both among I-O psychology practitioners and non-I-Os. As Schmidt, Van Dellen, and Islam (2025) identified ways in which films can support leadership development, popular culture may provide an intriguing approach to communicate I-O psychology’s value and as a methodological tool. Other social sciences, including social psychology, have started to utilize pop culture as a way to ground their studies in varying contexts; this technique may benefit I-O psychology research.

We would also encourage researchers and practitioners to continue to focus on these core human elements of the field and expand on what the meaning of I-O psychology work may be. By bringing our science into new contexts and new kinds of work, whether gig work or the fight for decent work, we can help to keep the field of I-O psychology vibrant. No matter what the future of I-O psychology, academics, practitioners, and students would do well to heed the words of Rick Grimes from Season 8, Episode 1 of The Walking Dead, “If we start tomorrow right now, no matter what comes next, we’ve won.”

References

Bal., P. M., Dóci, E., Lub, X., Van Rossenberg, Y. G. T., Nijs, S., Achnak, S., Briner, R. B., Brookes, A., Chudzikowski, K., De Cooman, R., De Gieter, S., De Jong, J., De Jong, S. B., Dorenbosch, L., Galugahi, M. A. G., Hack-Polay, D., Hofmans, J., Hornung, S., Khuda, K.,…Van Zelst, M. (2019). Manifesto for the future of work and organizational psychology. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1602041

Bijker, R., Merkouris, S. S., Dowling, N. A., & Rodda, S. N. (2024). ChatGPT for automated qualitative research: Content analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26(1), e59050. https://doi.org/10.2196/59050

Blustein, D. L., Lysova, E. I., & Duffy, R. D. (2023). Understanding decent work and meaningful work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031921-024847

Carr, S. C. (2025). Humanitarian work psychology: Research with underrepresented and forgotten

populations. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 13.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

Cho, J., & Lee, E.-H. (2014). Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. Qualitative Report, 19(32), 1. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1028

Cope, D. G. (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(1), 89–91. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.89-91

Cropanzano, R., Keplinger, K., Lambert, B. K., Caza, B., & Ashford, S. J. (2023). The organizational psychology of gig work: An integrative conceptual review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(3), 492–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001029

Dickey, D. (2020). Twenty-first century fear: Modern anxiety as expressed through postapocalyptic literature. Macksey Journal, 1(1).

Dillon, S., Courey, K. A., Chen, Y. R., & Banerjee, N. J. (2023). Future-proofing I-O psychology: The need for updated graduate curriculum. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(1), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.110

Fletcher, K. A. (2025). Think of the children: A call for mainstream organizational research on child employment and labor. Occupational Health Science, 9(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-024-00201-2

Follmer, K. B., Sabat, I. E., Jones, K. P., & King, E. (2024). Under attack: Why and how I-O psychologists should counteract threats to DEI in education and organizations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 17(4), 452–475.

Hanges, P. J., Salmon, E. D., & Aiken, J. R. (2013). Legal issues in industrial testing and assessment. In K. F. Geisinger, B. A. Bracken, J. F. Carlson, J.-I. C. Hansen, N. R. Kuncel, S. P. Reise, & M. C. Rodriguez (Eds.), APA handbook of testing and assessment in psychology, Vol. 1. Test theory and testing and assessment in industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 693–711). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14047-038

Islam, S., Schmidt, G. B., Pervez, H., DeRosa, J., Carpenter, V., Albert, Y., Ingram, C. (2022). Ask me anything (AMA) about graduate school: How online and brick-and-mortar programs are viewed on the I-O psychology reddit. The Industrial Organizational Psychologist, 59(4). https://www.siop.org/tip-article/ask-me-anything-ama-about-graduate-school-how-online-and-brick-and-mortar-programs-are-viewed-on-the-i-o-psychology-reddit/

Jonsen, K., & Jehn, K. A. (2009). Using triangulation to validate themes in qualitative studies. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 4(2), 123–150. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640910978391

Katz, I. M., & Rauvola, R. S. (2025). Turbulent times, targeted insights: I-O psychology’s response to policy shifts. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 18(3), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2025.10046

Keith, M. G., Strah, N., & Sorensen, M. B. (2025). The beginning of the end for equal employment opportunity? What the repeal of EO 11246 means for organizations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 18(3), 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2025.10023

Khan, Z. A., Swaminathan, B., Prakash, S., Jayanthi, S., & Kumari, R. (2025). ChatGPT and sentiment analysis: Unveiling emotional insights in textual data. Procedia Computer Science, 259, 52–60.

Krasna, H., Czabanowska, K., Jiang, S., Khadka, S., Morita, H., Kornfeld, J., & Shaman, J. (2020). The future of careers at the intersection of climate change and public health: What can job postings and an employer survey tell us? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041310

Landis, R. S., Fogli, L., & Goldberg, E. (1998). Future-oriented job analysis: A description of the process and its organizational implications. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 6(3), 192–198.

Landers, R. N. (2017, July 19). Dominance of SIOP membership by online-degree holders coming [Blogpost]. NeoAcademic. https://neoacademic.com/2017/07/19/dominance-of-siop-membership-by-online-degree-holders-coming/

Lefkowitz, J. (2008). To prosper, organizational psychology should… expand the values of organizational psychology to match the quality of its ethics. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 29(4), 439–453.

Lefkowitz, J. (2010). Industrial-organizational psychology’s recurring identity crises: It’s a values issue! Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 3(3), 293–299.

Lefkowitz, J. (2019). The conundrum of industrial-organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 12(4), 473–478. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2019.114

Maier, D., Waldherr, A., Miltner, P., Wiedemann, G., Niekler, A., Keinert, A., Pfetsch, B., Heyer, G., Reber, U., Häussler, T., Schmid-Petri, H., & Adam, S. (2018). Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: Toward a valid and reliable methodology. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(2–3), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2018.1430754

Maudlin, J. G., & Sandlin, J. A. (2015). Pop culture pedagogies: Process and praxis. Educational Studies, 51(5), 368–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131946.2015.1075992

Mitra, R., & Fyke, J. P. (2017). Popular culture and organizations. In C. Scott, & L. Lewis (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of organizational communication. Wiley-Blackwell.

Moon, H. (2014). The postapocalyptic turn: A study of contemporary apocalyptic and postapocalyptic narrative. Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee.

Mumby, D. K. (2019). Work: What is it good for? (Absolutely nothing)—a critical theorist’s perspective. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 12(4), 429–443. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2019.69

Ones, D. S., Kaiser, R. B., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Svensson, C. (2017). Has industrial-organizational psychology lost its way? Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology. https://www.siop.org/Research-Publications/Items-of-Interest/ArtMID/19366/ArticleID/1550/Has-Industrial-Organizational-Psychology-Lost-Its-Way

Rehn, A. (2008). Pop (culture) goes the organization: On highbrow, lowbrow and hybrids in studying popular culture within organization studies. Organization, 15(5), 765–783.

Rhodes, C., & Westwood, R. (2008). Critical representations of work and organization in popular culture. Routledge.

Roberts, D. L. (2020). The psychology of dystopian and postapocalyptic stories: The proverbial question of whether life will imitate art. International Bulletin of Political Psychology, 20(2), 1–7.

Rose, K. (2014). Adopting industrial organizational psychology for eco sustainability. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 20, 533–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.066

Rotolo, C. T., Church, A. H., Adler, S., Smither, J. W., Colquitt, A. L., Shull, A. C., Paul, K. B., & Foster, G. (2018). Putting an end to bad talent management: A call to action for the field of industrial and organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 11(2), 176–219. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2018.6

Rudolph, C. W., Allan, B., Clark, M., Hertel, G., Hirschi, A., Kunze, F., Shockley, K., Shoss, M., Sonnentag, S., & Zacher, H. (2021). Pandemics: Implications for research and practice in industrial and organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 14(1–2), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2020.48

Schmidt, G. B., Van Dellen, S. A., & Islam, S. (2025). Ready, set, leadership development! Using films in developing leaders. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2025(185), 39–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20656

Sinclair, S., & Rockwell, G. (2016). Voyant tools. http://voyant-tools.org/

Sinclair, S. J., & Silbersweig, D. A. (2025). Apocalypse now? Mortality and mental health correlates of the Doomsday Clock. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 81(2), 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2024.2439762

Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology. (2016). Guidelines for education and training in industrial-organizational psychology. Author. https://www.siop.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/SIOP_ET_Guidelines_2017.pdf

Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology. (2025, May 20). SIOP issues statement on Title VII and job-relevant employment practices. https://www.siop.org/post/siop-issues-statement-on-title-vii-and-job-relevant-employment-practices/

Vezzali, L., McKeown, S., McCauley, P., Stathi, S., Di Bernardo, G. A., Cadamuro, A., Cozzolino, V., & Trifiletti, E. (2021). May the odds be ever in your favor: The Hunger Games and the fight for a more equal society. (Negative) media vicarious contact and collective action. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12721

Wachinger, J., Bärnighausen, K., Schäfer, L. N., Scott, K., & McMahon, S. A. (2025). Prompts, pearls, imperfections: Comparing ChatGPT and a human researcher in qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 35(9), 951–966.

Wang, Z., Xie, Q., Feng, Y., Ding, Z., Yang, Z., & Xia, R. (2023). Is ChatGPT a good sentiment analyzer? A preliminary study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.04339. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.04339

Appendix A

Survey Instrument

Informed consent

Title of research: I-O psychology in a postapocalyptic world

Principle Investigator: Sy Islam, Talent Metrics Consulting

- Introduction and purpose of the study

This study is being conducted to understand how I-O psychology practitioners and academics view the role of I-O psychology in a postapocalyptic world as often depicted in popular media (i.e., The Walking Dead, Mad Max, Fallout, The Last Of Us)

- Description of the research

This study involves participation in a 10-minute survey that includes both open-ended and close-ended questions about the role of I-O psychology in a postapocalyptic world.

- Potential risks and discomforts

There are no known risks to this study

- Potential benefits

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very useful | Useful | Somewhat useful | Not useful | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The potential benefits in participating in this study is you may enjoy imagining the use of I-O psychology in a nontraditional environment. The field of I-O psychology may benefit from this exercise, and we may find new ways to think about what I-O psychology has to offer.

The researchers intend to submit the findings to TIP (The Industrial Organizational Psychologist), the official publication of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology that is posted quarterly.

*1. Please type your name below to indicate consent. Your responses will be kept confidential. Thank you for participating in this study. We are researchers interested in different contexts where I-O psychology may be used. The purpose of this study is to understand how the core skills of I-O psychology may be used in a postapocalyptic context. A “postapocalyptic world” refers to a setting or society that exists after a catastrophic event, like a large-scale war, natural disaster, or pandemic, where civilization has been significantly destroyed or severely disrupted, leaving survivors to navigate a drastically changed and often dangerous environment; essentially, a world after the apocalypse.

- Please describe your postapocalyptic world. Examples from popular culture include those depicted in Mad Max, The Walking Dead, The Last of Us, and Fallout. However, feel free to create a unique vision that reflects your own interpretation of a postapocalyptic world.

- How might an I-O psychologist contribute to the postapocalyptic world you describe?

|

- Where do you spend 51% of your work as an I-O (Select one option)

Academia (i.e. university professor, administrator)

Practitioner (i.e. external or internal consultant)

Current graduate student (MA/PhD)

Other (Please specify) __________

Volume

63

Number

3

Author

Sayeedul Islam, Farmingdale State College/Talent Metrics Consulting; Giselle Hajir, Talent Metrics Consulting/George Mason University; Khang Doan, University of Central Florida; & Michael Chetta, Talent Metrics Consulting/University of Central Florida

Topic

Future of Work